Many probably know that frequent commits are bad and slow, but how bad and how slow is not clear, and this small test is designed to demonstrate the impact of this event.

I’ll note right away that commits should be made exactly when the business process requires it, or when there is any other significant reason, rather than just ‘in case.’

Test environment:

Oracle 19.23

OS: OEL 8.5 4.18.0-513.24.1.el8_9.x86_64

RAM: 128GB

CPU: AMD Threadripper 1920x

Disks:

Disk group for data files: +ORADATA: SATA SSD GeIL R3 512GB

Disk group for redo logs: +ADATAD1: XPG GAMMIX S11 Pro PCI E 3.0 x4

Disk group for archive logs: +ARCHLOG: SATA SSD GeIL R3 512GB

+ORADATA and +ARCHLOG are located on the same physical disk SATA SSD GeIL R3 512GB.

The code that will act as the load (intensive business process activity):

Variant 1:

declare

v_loop number;

v_seq number;

v_text varchar2(3000);

v_rtext varchar2(3000);

begin

execute immediate 'truncate table t1';

dbms_output.put_line('Start: '||to_char(sysdate,'dd.mm.yyyy hh24:mi:ss'));

dbms_workload_repository.create_snapshot;

v_loop:=1;

select dbms_random.string(opt => 'X',len => 3000) into v_rtext from dual;

while v_loop<5000001

loop

v_seq:=t1_seq.nextval;

insert into t1(id,text) values(v_seq,v_rtext);

commit write wait;

select t1.text into v_text from t1 where id=v_seq;

update t1 set t1.text='update' where id=v_seq;

commit write wait;

delete from t1 where id=v_seq;

commit write wait;

v_loop:=v_loop+1;

end loop;

dbms_workload_repository.create_snapshot;

dbms_output.put_line('End: '||to_char(sysdate,'dd.mm.yyyy hh24:mi:ss'));

end;Variant 2:

declare

v_loop number;

v_seq number;

v_text varchar2(3000);

v_rtext varchar2(3000);

begin

execute immediate 'truncate table t1';

dbms_output.put_line('Start: '||to_char(sysdate,'dd.mm.yyyy hh24:mi:ss'));

dbms_workload_repository.create_snapshot;

v_loop:=1;

select dbms_random.string(opt => 'X',len => 3000) into v_rtext from dual;

while v_loop<5000001

loop

v_seq:=t1_seq.nextval;

insert into t1(id,text) values(v_seq,v_rtext);

select t1.text into v_text from t1 where id=v_seq;

update t1 set t1.text='update' where id=v_seq;

delete from t1 where id=v_seq;

commit write wait;

v_loop:=v_loop+1;

end loop;

dbms_workload_repository.create_snapshot;

dbms_output.put_line('End: '||to_char(sysdate,'dd.mm.yyyy hh24:mi:ss'));

end;The difference between the first and second options is that the first option has 3 commits within the loop, while the second has 1 commit within the loop. Also, the ‘commit write wait’ construct is chosen to avoid PL/SQL optimization, as this commit variant is used if the code is not written in PL/SQL.

Variant 1 took 23 minutes and 6 seconds (1386 seconds) to complete.

Variant 2 took 12 minutes and 51 seconds (771 seconds) to complete.

Variant 3 (commit executed only at the end of the loop) took 503 seconds, but it’s not considered for evaluation.

So, Variant 2 is nearly twice as fast.

Reasons why Variant 1 took longer:

Further calculations are done with a certain margin of error, and it is assumed that all statistics relate only to the tasks being performed.

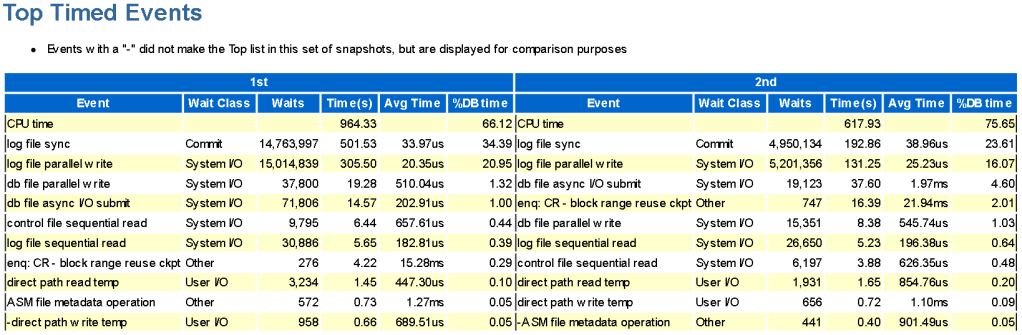

Variant 1 took 501 seconds for log file sync (lfs) out of 1386 seconds, while variant 2 took 192 seconds for log file sync (lfs) out of 771 seconds. By subtracting 501 from 1386, we get 885 seconds. Mathematically excluding all intermediate commits in the loop from variant 1, it still takes more time than variant 2, with 885 seconds versus 771 seconds.

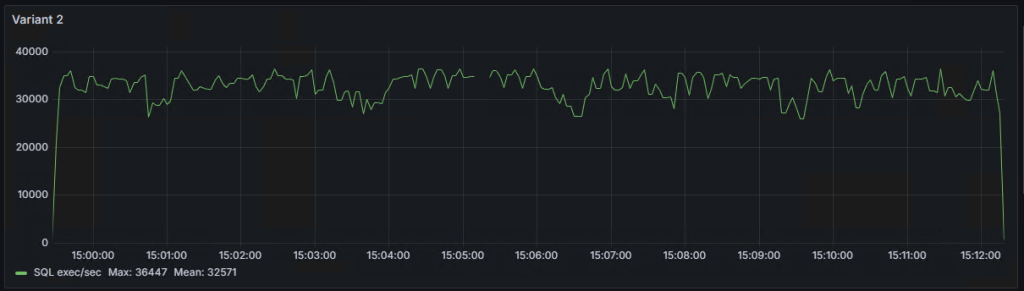

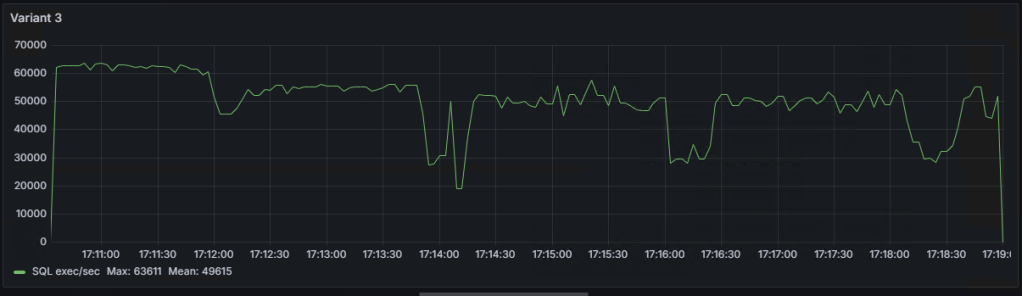

Graph of the number of SQL statement executions per second for ‘Variant 1,’ ‘Variant 2,’ and ‘Variant 3’:

As seen on the graphs, there are some ‘dips,’ the explanations for which I will try to provide in the following note.